There are days in automotive when everything seems to be going smoothly. And then… the phone rings. It’s production or logistics, calling to say that the material, process, or label doesn’t match what was approved. Suddenly, you’re playing for high stakes: deliver on time, keep the customer, maintain system compliance, and—most importantly—avoid a nonconformity that could blow up during the very next audit.

That’s exactly when deviation management steps in. In the right hands, it’s not an excuse for failure—it’s a real, controlled method of risk mitigation and ensuring business continuity.

Deviation management – when and why do we need it?

Production “here and now” vs. quality and compliance

Automotive is an extreme sport—just without the helmet. On one side: deadline pressure, shipping plans, customers waiting for parts “yesterday.” On the other: quality requirements, certifications, audits, and documentation that needs to be pixel-perfect.

And then comes the moment that everyone who’s ever been near a production line knows:

-

“We have a different material than what was approved, but the customer can’t wait”

-

“We moved the tooling to another hall because the press in the original location broke down”

-

“Our sub-supplier changed the process and now the surface roughness of the part has changed. What do we do?”

What do you do? You produce—because you have to. But… are you allowed to?

When is it allowed—and when is it not—to produce with a deviation?

This is where deviation management comes into play—not as an excuse, but as a formal, controlled process that allows you to navigate the situation by the book. But be careful—not every case qualifies for a “rubber stamp” deviation. There are limits.

You can produce with a deviation if:

-

You have customer approval for the specific scope of the deviation (e.g. color, material, production location),

-

The deviation is time-limited or quantity-limited (less common), with a clearly defined expiration date and return-to-compliance plan,

-

The organization has managed the risk, e.g. with additional inspections, sorting, or notifying the customer’s SQE,

-

Everything is documented—approval, risk analysis, containment actions, and communication trail.

You cannot produce with a deviation if:

-

The customer has not been informed, has not approved, or has not given consent,

-

You act on your own initiative because “it looks fine, and we’ve been doing it like this for years.”

Deviation management isn’t a loophole for breaking rules—it’s a survival tool in critical situations, but only if you know how to use it. A well-managed deviation can save a shipment, your cash flow, and your customer relationship. A poorly managed one can trigger a cascade of problems: complaints, audit findings, and loss of trust.

What Is a Deviation and What Are Its Types?

In the automotive industry, the term “deviation” (or sometimes “interim approval”) is still often misunderstood and wrongly associated with covering up mistakes. In reality, when properly implemented, a deviation is a conscious decision made by the organization to temporarily operate outside of established requirements. Nothing more, nothing less.

It’s not about cutting corners — it’s an contingency plan that allows the company to keep moving without falling out of system or quality compliance. And more importantly — without losing customer trust.

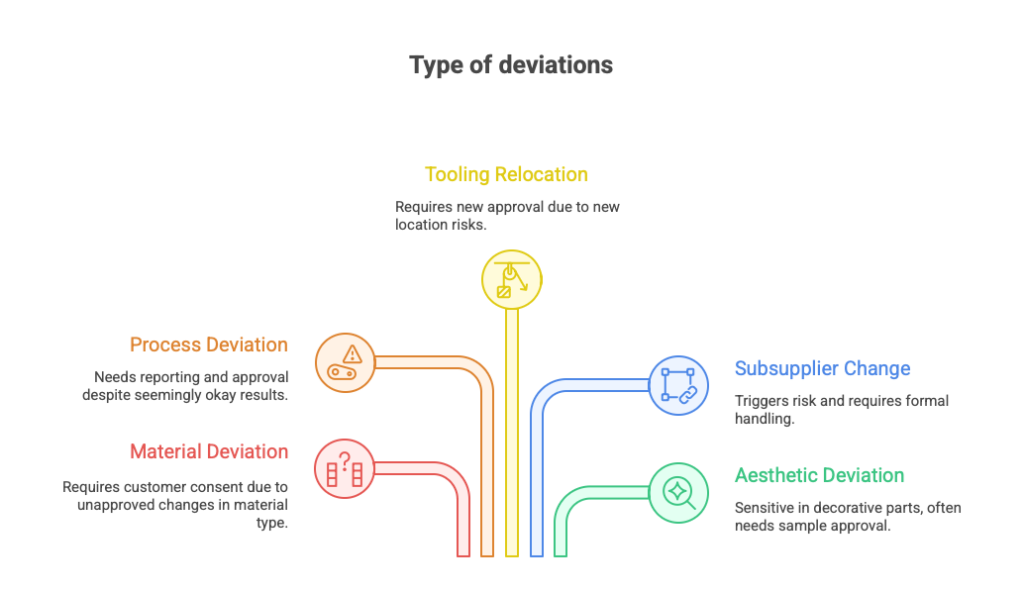

Types of Deviations – What Can Go Differently Than Planned?

Not all deviations are created equal. In practice, they can be categorized into several groups — each with different risk levels, approval requirements, and visibility in the eyes of the customer or auditor.

Material Deviation

A change in material type, alloy, coating, or protective layer. A classic. Example: instead of the approved PA6 plastic, you receive PA6-GF30. Technically better, sure — but not approved. Without customer consent: don’t even touch it.

Process Deviation

A change in process parameters (e.g. welding time, injection temperature, heat treatment method) or switching from one method to another (e.g. manual instead of automated assembly). Even if the part “comes out OK” — it still needs to be reported and approved.

Tooling Relocation Deviation

Machines are moved from one hall to another. Or from China to Poland. Technically it’s “the same process, same equipment.” But for the customer — it’s a completely new location, which means new risks.

If the Tooling Kick Off or PPAP covered a different site — you’ll need new approval or a deviation.

Subsupplier Change Deviation

Your subsupplier changed their process or location. Or you’re launching a brand new one. Same part number — but different process chain. This triggers risk for the customer and almost always requires formal deviation handling.

Aesthetic Deviation

The product technically meets its function, but its appearance is slightly off — different texture, gloss, or a shade that’s just a bit outside the approved master.

This is especially sensitive in decorative or premium parts. Often, the customer will request individual evaluation — sometimes even physical sample approval.

Any change that goes beyond the approved scope of PPAP, Tooling Kick Off, or CSR may require a formal deviation. It won’t always be a “system disaster” — but if you don’t handle it correctly, even a minor deviation can come back to bite you. And as we all know — making the part is rarely the hard part.

Explaining it to the customer or auditor later? That’s where the pain begins.

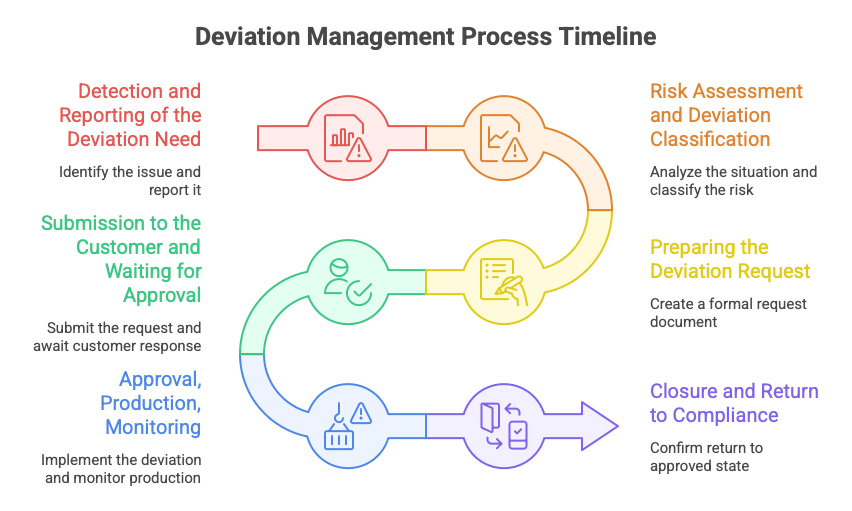

Deviation Management – Step-by-Step Process

It usually starts innocently enough. Someone on the production floor notices that the material delivered by the subsupplier has a different batch number than usual. Or process engineering reports that due to a failure, the tooling needs to be moved to a different line. Or SQE informs you: “New plating supplier – the previous one has exited the market.”

At this point, the warning light goes off: is this still within the approved PPAP scope?

If not – the deviation procedure must be initiated. And keep in mind – timing matters. Good deviation management is not just about whether the customer will approve, but whether you’ll resolve it before the production halt starts costing thousands of euros per day.

Step 1: Detection and Reporting of the Deviation Need

The need for a deviation can originate from many areas within the organization. Often, it starts on the shop floor – due to a technical problem, tooling failure, or a temporary change in workstation location. The signal may also come from supplier quality, for instance when a subsupplier changes their process, location, or material.

In new project launches, deviations may result from schedule changes. In current production, the need may arise due to tooling relocation. Logistics may also raise a deviation request – for example, when the approved material is unavailable and only an alternative is on hand.

Step 2: Risk Assessment and Deviation Classification

The quality team – sometimes supported by a process engineer, project manager, or SQE – analyzes the situation:

-

What exactly is changing? (material, process, location, supplier…)

-

Does the final product still meet its function, safety, and visual requirements?

-

Has the customer classified similar situations as critical?

-

What risk mitigation actions can be implemented? (e.g. extra controls, samples, sorting)

If the evaluation indicates an impact on customer requirements, a deviation with formal customer approval is needed.

Step 3: Preparing the Deviation Request

This shouldn’t be just a “Hey, is this okay?” email. A proper deviation request is a formal document (or a dedicated client portal form) that includes:

-

Part number, customer change number, PPAP number (if applicable)

-

Deviation description (what is changing and why)

-

Validity period (from–to) – in some niche cases, quantity-based deviations are accepted (e.g. for sunroofs or 4×4 variants)

-

Return-to-conformity plan

-

Control measures (e.g. 100% inspection, additional testing)

-

Risk analysis and potential customer impact

-

Attachments (measurement report, samples, photos, etc.)

Step 4: Submission to the Customer and Waiting for Approval

This is a critical step – and communication is key. A good quality engineer doesn’t just send the document, but:

-

Prepares the customer by giving early notice (ideally with brief context),

-

Tracks the request – follows up, responds to SQE questions,

-

Negotiates, if needed – sometimes the customer proposes a compromise (e.g. approval only for certain end customers, regions, or for a limited time).

Meanwhile, production is often on standby – waiting for the green light – which is why close follow-up is crucial. You don’t want this to disappear into the email void.

Step 5: Approval, Production, Monitoring

Once the customer approves the deviation, everything must be clearly identified and tracked:

-

Production must stay within the approved scope (quantities, dates, content),

-

Each batch must be labeled as “produced under deviation” (on labels, in ERP, in delivery documents),

-

Additional quality checks must be implemented as per the deviation request,

-

Shipping must comply with customer expectations – sometimes this includes sending samples and/or separate confirmation to the SQE.

Step 6: Closure and Return to Compliance

When the deviation’s validity period ends, formal closure is required. First, you must confirm that the process, material, or location has returned to the approved state or been newly approved.

Then, document the closure of the deviation – often with customer confirmation, which can be in the form of a signature, email, or digital acceptance. If the issue was complex or had an impact on product function, it’s recommended to update your Lessons Learned database to prevent recurrence.

Also critical: prevent the so-called “second life” of a deviation — meaning unauthorized production beyond the approved time window. That’s where serious audit findings tend to come from.

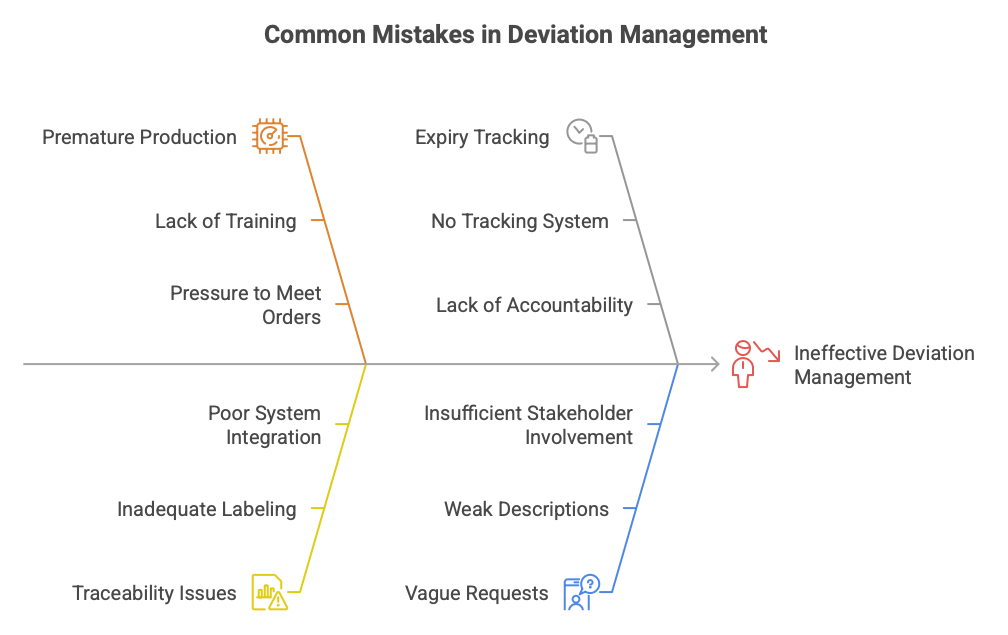

Deviation Management – Common Mistakes and Good Practices

Deviation management isn’t rocket science — but like every procedure in automotive, it comes with its own traps. In this section, I’ll walk you through the most common mistakes companies make, along with practical, battle-tested methods that don’t just help you avoid “system failures,” but also build long-term customer trust.

Mistake 1: Producing Before the Deviation Is Approved

This happens more often than you think. Production is rolling, orders are piling up, and someone makes the call:

“Let’s build it now and sort out the paperwork later.”

The risk? If the customer doesn’t approve the deviation, the entire batch may need to be scrapped or sorted — at your own expense.

Good practice: Train your production teams and make the rule clear: No written customer approval = No production under deviation.

Mistake 2: No Traceability of Deviation Batches

Batches produced under an active deviation must be clearly identified — physically or in the system — and labeled appropriately.

If not, the auditor (or worse, the customer) will ask: “How do you know this batch was produced under deviation?”

Good practice:

-

Dedicated labels with “Deviation approved” clearly marked

-

Deviation number registered in the ERP or MES system

-

Delivery documents referencing the deviation approval

Even the best Excel file won’t help you in a crisis if you can’t show physical or digital evidence.

Mistake 3: Not Tracking the Deviation Expiry Date

Deviations have end dates. Yet in many companies, no one tracks them — and no system sends reminders. So production continues… and a week later, you’re hit with the question: “Wait, was that deviation still valid?”

Good practice:

-

Deviation register with automated reminders (e.g. X days before expiry)

-

Tasks assigned in Trello, Jira, Outlook, or even Microsoft Teams

-

Daily communication during shopfloor or management stand-ups

-

Clear ownership — someone specific is accountable for closing deviations

(Not just “someone from quality.”)

Mistake 4: Vague Deviation Requests Sent to the Customer

If the customer doesn’t clearly understand what you’re changing and why, they won’t approve — or you’ll get 5 follow-up emails asking for clarification.

Weak descriptions like “process change at supplier” without detail are red flags.

What worked for me: I started inviting all stakeholders to a quick call or meeting where we would align on the exact deviation content. Then, each party would approve it electronically in the system. This not only clarified the scope, but reduced the back-and-forth and improved trust.

Mistake 5: “It’s Just a Running Change…”

Yeah, I’ve heard that one before. At one production site I worked with, someone from management would often use the term “running change” to bypass the formal deviation process required by the customer.

Now, don’t get me wrong — the automotive world isn’t black and white. But in these situations, I always made a point to say — very clearly in meetings: “If we do this too often, we risk a New Business Hold and might end up being the ‘hero’ of the month in the escalation report.”

And you know what? Most of the time, that was all it took to realign the team.

How to Prepare for an Audit When You Have Active Deviations

You have an active deviation, and then—bam—a message arrives: your customer or an IATF auditor is coming. Your heart rate spikes, because you know that deviations are often a “hot potato” during audits. But relax—there’s nothing to fear if you know how to prepare.

Auditors don’t expect a perfect world. What they expect is transparency and control.

What will the auditor want to know?

An auditor will ask exactly the same questions you should be asking yourself before they show up:

-

Do you have up-to-date documentation of the deviation?

-

Did the customer actually approve the deviation?

-

Where are the batches produced under deviation?

-

How do you monitor the status and expiration of the deviation?

-

Have preventive actions been taken to avoid recurrence?

One of the most common audit techniques is to ask open-ended questions. So don’t be surprised if you hear: “How is deviation management handled at your site?” If your answer is “I’m not sure,” you’re opening the door to a nonconformity.

1. Prepare Complete Documentation

It’s not enough to have an email — you need a formal approval and complete supporting documentation confirming the customer’s consent. In many organizations, documents are scattered across inboxes, flash drives, and random SharePoint folders.

Your minimum documentation package should include:

-

A copy of customer approval (email, form, or portal entry)

-

Clear and specific description of the deviation (in English, if required)

-

Start and end dates of the deviation

-

Assessment of impact on product function and quality, plus risk analysis

-

Attachments: photos, measurements, test reports, IMDS, action plans

-

Batch tracking (production order numbers, production dates, IDs, labels)

2. Ensure Proper Traceability

The auditor may ask: “How do you distinguish deviation batches from regular ones?” If your answer is “The warehouse guy knows,” you’re in trouble.

Good practices:

-

Labels with deviation number

-

Separate storage area

-

Barcode scan records or ERP traceability

This isn’t just a formality—it protects you from claim escalations if a customer discovers an issue on their production line.

3. Monitor Deviation Validity

A seasoned auditor might ask: “How do you know the deviation is still valid?”

Or:

“How do you ensure production hasn’t gone beyond the approved scope?”

What helps:

-

Deviation register with status and expiration dates (Excel or corporate QMS system)

-

Assigned person responsible for tracking and closure

-

Defined procedure for deviation closure

If the auditor sees a deviation that’s been “open” for 9 months, you can expect a major finding.

4. Show Customer Involvement

System auditors love the word “evidence.” Show that you’re not acting alone and you’ve kept the customer in the loop.

Examples of proof:

-

Email exchange with customer questions and replies

-

Notes from a virtual call (e.g. MS Teams or Zoom)

-

Deviation formally approved in the customer’s portal

If the customer knows, agreed, and it’s documented—you’re covered.

5. Cross-Functional Collaboration

Auditors pay close attention to interdepartmental communication. Show that the deviation didn’t sit quietly in the quality department.

Show involvement of:

-

Production (e.g. adjusted production schedules)

-

Logistics (e.g. monitored outbound shipments)

-

Customer Quality (e.g. contact with customer SQE)

-

Engineering (e.g. evaluated impact on functionality)

This shows maturity and systemic thinking in deviation handling.

Summary: Deviation Management Checklist for Audit Readiness

As experience shows — deviations are not rare exceptions. They are everyday reality. The difference between a mature organization and chaos is whether you have a plan, a procedure, and documentation — or just a “we’ll figure it out by phone” approach.

Here’s a practical checklist worth using anytime you need a deviation approved by your customer:

1. Change Documentation

-

Do you have a documented description of the change (process, supplier, location, tooling)?

-

Have you attached a detailed action plan with milestones or timeline?

2. Supplier Readiness Verification (optional but recommended)

-

Has the new supplier been formally assessed and approved?

3. Traceability and Logistics

-

Do you have a traceability plan for deviation batches?

-

Do you use specific labels and part markings (e.g. with deviation number)?

-

Has any layout change been documented (before/after)?

-

Do you have an updated packaging plan if applicable?

4. Customer Communication

-

Was the deviation submitted in advance (e.g. 90 days)?

-

Has the customer been formally notified (via portal, email, or meeting)?

-

Have you included photos, layout changes, and key contact details?

5. Closure and Lessons Learned

-

Is there a clearly defined deviation end date and return-to-compliance plan?

-

Have preventive actions been implemented and recorded in Lessons Learned?

-

Was the FMEA or Control Plan updated, if needed?

Final Thought

Customers don’t expect perfection. They expect predictability and control. If you can demonstrate that you’re managing deviations — even difficult ones — in a structured and responsible way, you’ll navigate even the biggest changes with confidence.

The good news? Most of these requirements can be standardized. The bad news? Only if you have a procedure in place — and a team that knows what it’s doing.

Author: Dariusz Kowalczyk