If you work in manufacturing, you know the moment: everything “lines up on paper,” yet the customer files a complaint, PPMs creep up, and the line stumbles on a simple changeover. Not because people are careless—but because we look at the company through departmental silos while the problem jumps between subcomponents, planning, production, inspection, and logistics like a spark through dry brush.

The process approach changes that perspective. Instead of “we have departments,” we say “we have a value stream”—from the RFQ (Request for Quotation), through manufacturing, all the way to warranty returns. Every part of that stream is a process with inputs, outputs, an owner, risks, and KPIs. It sounds simple, but it makes a big difference: fewer fires, more stable Cp/Cpk, shorter lead time, and launches that don’t end in customer escalations.

Yes—IATF 16949 and ISO 9001 expect a process approach. But we don’t do it “because the standard says so.” We do it because it’s the only way to keep quality under control given today’s supply-chain complexity and pressure on cost, timing, and PPM. Below is the essence: what the process approach is and why it’s a must-have in automotive.

What the Process Approach Is (and Why It’s a Must-Have in Automotive)

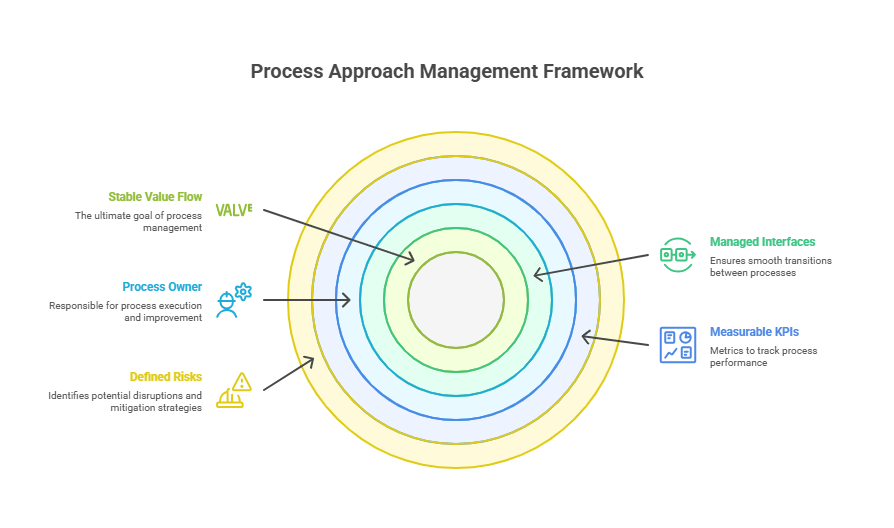

The process approach manages the organization as a network of interconnected processes, not isolated functions. Each process has clear inputs/outputs, a named Process Owner, measurable KPIs, defined risks, and—crucially—managed interfaces to upstream and downstream processes. The goal is a stable flow of value to the customer, measured by real outcomes (PPM, OEE, lead time), not just by how tidy the documentation looks.

What It Looks Like in Practice (Office and Shop Floor)

Value stream over silos: Customer order → planning → purchasing → incoming inspection → production prep → manufacturing → inspection → packing → shipping → after-sales support (in automotive, typically warranty return analysis). Each segment has its KPIs, but what matters is the performance of the whole flow.

A Process Owner instead of “accidental accountability”: Someone empowered to decide now, not “after the meeting.”

Interfaces that don’t leak: Exactly what Process A hands off to Process B—data formats, specifications, acceptable tolerances, approval status.

KPIs that drive action: Example—% of interim actions implemented after formal customer complaints.

Risk hooks that actually trigger updates: Clear triggers for FMEA and Control Plan revisions (supplier change, tool change, parameter shift, unauthorized trials on the line, etc.), and the discipline to use them.

Why It’s a Must-Have, Not a Nice-to-Have

1) Complexity and the speed of change

It takes just a “small” event—a new material batch with a nonconforming special characteristic, an injection parameter tweak, a revised drawing, or a different material index in SAP—to start a domino effect. Without a process map and managed interfaces, the issue “evaporates” between departments. With a process approach, you can see where and who touches the change and how it should be qualified (engineering change approval, PPAP, Run@Rate).

2) Customer requirements (CSR) + IATF/ISO

OEM expectations and their Customer-Specific Requirements (CSR) are, in practice, a test of process maturity: APQP, living FMEA, alignment with the Control Plan, process stability (SPC/MSA), readiness for VDA 6.3 or LPA. Without a process lens, you end up with documents that don’t agree with each other—or with reality.

3) Real results, not just “compliance”

A process approach shortens the learning loop: you spot trends earlier, adjust parameters faster, and stop rewriting the same 8D Report over and over. The result? More stable Cp/Cpk, lower scrap, fewer potential field returns, and PPAPs that clear without “weekend crisis mode”—I’ve had to live through that more than once.

4) Suppliers as part of your process

Your input is only as good as the interface with your supplier. If you treat the supplier like an “external random variable,” you don’t have a process—you have a lottery. A process approach here means supplier quality manages the flowdown: clear requirements, audits where needed, and fast escalation when a nonconformity hits the line.

Process maps aren’t wall art. They’re the operating system for how quality, production, logistics, and suppliers work together—so that “paper reality” matches shop-floor results.

60-Second Self-Check: Do You Really Run a Process Approach?

Could you sketch your process map on one page and point to the interfaces?

Does every key process have an empowered owner—not a “committee of goodwill”?

Do you know which KPIs are leading (what will happen) and which are lagging (what already happened)—and who presents them to leadership?

Are triggers for updating your FMEA/Control Plan clearly defined?

Does a supplier change automatically launch your formal change-management process—with clear evidence of re-validation ready for the customer?

Common Misconceptions (and How to Defuse Them)

“It’s just drawing a map.”

No. A map without an owner, KPIs, and triggers is an infographic. A process lives in decisions and reviews.

“Let’s add more inspection; that will fix it.”

Extra inspection adds cost and a false sense of safety. Stabilize the cause first, then adjust the control.

“Around here, everything depends on people.”

Exactly why you need a process. A good process supports people and reduces shift-to-shift variation.

If you answered “it depends” to any question—great starting point. A process approach begins with visibility and simple rules of the game.

From Organizational Context to a Process Landscape

Start with Organizational Context

Before you draw the first arrow, pause and describe the environment your company operates in. Context is a pragmatic snapshot: what you make and for whom, the conditions you play under, and what could “flip the table.”

This isn’t about quoting a standard. It’s about a few clear paragraphs you can read to a Production Manager or SQE without corporate jargon. If you supply two or three OEMs with different CSRs and a shaky supply chain, say it plainly. Add that materials vary (per lab results), batches are short, and CAD versions can change faster than the weekend shift roster. This “playing field” feeds into the strategic process sheet and the management review—so everyone finally plays the same game.

Stakeholders and Their Influence

Stakeholders are those who actually shape your processes. On one side: customers with their CSRs, PPAP expectations, Run@Rate, traceability, or LPA (e.g., Stellantis). On the other: suppliers and subsuppliers whose input quality determines whether your process is predictable. Around them: regulations, EHS, and material requirements. Inside: your internal “customers”—production, logistics, maintenance, metrology. Each expects something and delivers something. Naming this makes closing process interfaces far easier later.

System Boundaries (Scope) and Remote Interfaces

Next, define the scope of the quality system. In practice: what’s “inside” (locations, product families, processes you own) and what’s “outside” (outsourced steps, special processes, or remote functions like global design or central purchasing). If drawings and the BOM (Bill of Materials) are maintained by another site or a global team, describe the interface and who owns the data quality.

Identify Value Streams

Once the context is clear, map value streams. Most companies don’t flow down a single river. You’ll usually find 2–4 distinct streams that differ by technology, product families, or order-fulfillment model. “Injection–paint–assembly” behaves differently from “stamping–welding–assembly,” and prototypes/short runs are different again.

Separate them, then run each stream through the same motion: from RFQ via APQP and purchasing, incoming, production, and inspection to shipping and warranty. You avoid one giant “everything map” and get a few sensible routes instead.

Three Process Layers: Core, Support, Management

Now name the processes and organize them in three layers:

Core (value-creating): customer requirements management, APQP/NPI (with all the engineering “kitchen work”), purchasing & SQM, planning & logistics, manufacturing, inspection & validation, shipping & customer service.

Support: maintenance & calibrations, IT (incl. cybersecurity/TISAX, increasingly required in automotive), HR (competency matrices & qualifications), EHS, infrastructure.

Management: strategy, goal cascade, management review, internal audits & LPA (if deployed), plus the umbrella of change and risk management.

Write short paragraphs instead of just lists—you’ll see how value flows and where the pipe most often clogs.

The Process Approach Also Needs a Thoughtful One-Pager

The outcome should be a practical one-pager—a single-page process map. At the top, a concise context block: what you do, for whom, and your biggest risks (you can also keep this as a separate doc).

Guide the reader’s eye across the three layers: management on top, core in the middle, support at the bottom. Arrows don’t need to be art—just clear about what moves from A to B: a production plan with the correct drawing revision; a complete measurement set from metrology.

Treat the map as the index to your process sheets.

The Process Sheet — Minimum Viable Standard

No poetry—just completeness. Start with the objective (“what we deliver and for whom”). Define inputs and outputs, including a clear Definition of Done. Name an owner with real authority. Set KPIs (e.g., APQP on-time rate, customer PPM).

Mark risks and triggers that automatically start the formal change-management process. Link the quality tools: which parts of PFMEA and the Control Plan this process touches, what measurements are under MSA (e.g., NDC thresholds), where you store evidence and how you version it. Close with critical resources and competencies—people, machines, software—because without them even the best plan stays on paper.

Process Interfaces and the Definition of Done

Interfaces are where things usually break. Instead of “we hand over a file,” define what “done” really means. When the AQE (Advanced Quality Engineer) passes the baton to Purchasing/SQM, they hand over a frozen data pack: correct drawing revision, current Control Plan, FMEA outputs, material specs, and labeling requirements.

Metrology, handing off to Production, clearly confirms calibrations are current, measurements meet NDC requirements, and the next verification is scheduled. Production, passing a lot to final inspection, provides a complete lot card with traceability, confirms parameters were within window, and that no nonconformities are open.

Logistics, before shipping, ensures PPAP docs are complete and labels are customer-compliant. Capture this in a paragraph in the process sheet and back it up with a simple handoff checklist—less romantic, more effective.

How to Pull This Together in 90 Minutes

You don’t need a week of workshops. One focused session can do it: start with a short, shared context. Name 2–4 value streams (don’t mix technologies or order types). Sketch the three-layer blocks and discuss the few interfaces that truly decide flow.

Finish by assigning owners and one lead/lag KPI per process, and set a review cadence. You’ll leave with a first draft of the process map and the seeds of your process sheets; the rest is refinement and putting it to work day to day.

Author: Dariusz Kowalczyk